After reading Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Talking to Strangers—What We Should Know about the People We Don’t Know—I thought it might be helpful to look at this issue in a more positive light. Gladwell shares a series of horrifying stories that resulted from not having skills to discern the actions or language of others we work with who have sinister intent. His accounts go way beyond the simple saboteur many have encountered in the workplace, who as Hank Rubin describes can be one of several personality types including the malicious, or limelight, or power-grabbing, or lone wolf saboteur. Gladwell posits that culturally in the US, we have yet to be trained to identify or seek evidence that exposes the liar, the predator, or the spy.

But I would propose that we haven’t been trained to learn about others in our environments that we “know” or to work with them. Time is one barrier, but the lack of convenient means of talking with people about their work and learning about their interests, skills, passions, past projects, etc. hampers our ability to work with them in collaborative ways. Those born digital carry their “known” people in their phone. Why strike up a conversation with someone in line at Starbucks or at the dog park if you can converse with others electronically that you already have ties to?

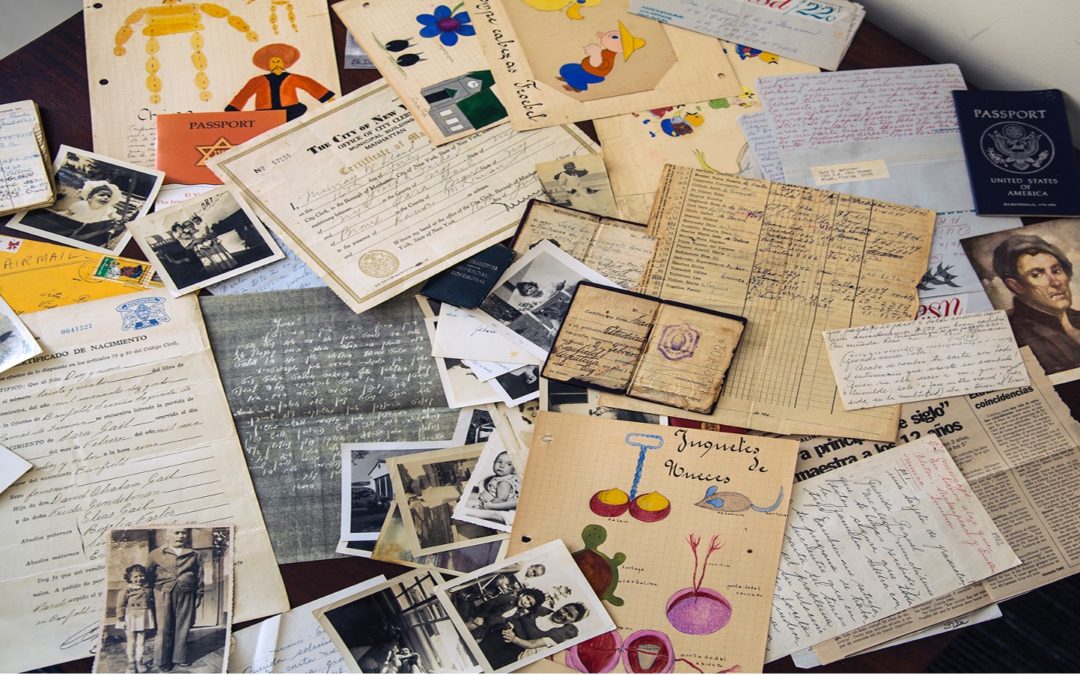

Think about the last time you met someone you didn’t really know but who worked in your environment. Were you surprised at what you learned about them? Their interests or their latest projects? This happened to me recently when I was introduced to Martha Kapalewski, the new bilingual archivist at the University of Florida Libraries. She asked what I was doing at the libraries and I shared that I was reading letters my mother had written in Spanish that were included in my family’s archive of Jewish immigrant materials. Martha was fascinated and then happened to stop by the Judaica Library to speak to curator, Rebecca Jefferson, while I was still reading. Rebecca and I showed her the contents of one box—she was thrilled to see materials created by my mother, Sara Gail de Farber, in the 1930s while she was enrolled in an early childhood master degree program in the University of La Plata, Argentina. Her mother had recently passed and as an archivist she was touched to see that I had preserved these materials for others to learn from. We have since been in touch—Martha is planning to work with the archive to expose my mother’s works and to share the importance of preserving family papers. Our next step is to meet for tea and chat about our mothers.